Photo: Thomas Dutour

Five years after the 2015 Gorkha earthquake, and despite the great efforts by Nepalese authorities, numerous families remained displaced. Delving into the situation, our team uncovered how well-intentioned post disaster recovery policies might fall short in addressing the needs of certain individuals or groups by overlooking context-specific problems, such as income, workplace disruption or even social gender bias. Now, their research is opening a path to designing more effective disaster risk reduction policies by addressing the impacts which are relevant in a specific region and for local communities in case of disaster.

Disaster risk assessment and modelling goes beyond assessing financial loss and damage to infrastructure.

Living in the same neighbourhood and in similar houses, the Adhikaris and the Thapas were amongst the almost 3.5 million people who saw their homes damaged or destroyed during the 2015 M7.8 earthquake. With both houses experiencing similar damage, they became part of the 2.6 million internally displaced Nepalese. Similarities stop here though, as their post-earthquake experiences were very different.

While the Adhikaris workplace in a nearby factory crumbled and they grappled with financial hardship, the Thapas, employed in a company providing services for local banks which sustained the seismic upheaval, had an operational workplace, allowing them to sustain a degree of stability in their lives. After the earthquake, both families received comparable financial support from the government for home reconstruction. That support, together with their own income, allowed the Thapas to reconstruct their home not long after the disaster. In contrast the Adhikaris remained in temporary accommodation for an extended period. This difference in recovery experiences highlights the role of social vulnerability: while one family dealing with job loss and financial uncertainty, faced a more challenging road to recovery, the other, with sustained employment, had a more stable foundation for rebuilding. This, even though both families experienced similar damage to their households.

Aftermath of Nepal Earthquake in Kathmandu. Photo: Thomas Dutour.

This narrative is fictional. Still, its proximity to reality is underscored by numerous studies (see box) revealing the disparate impact of disasters on various social groups and how existing inequalities tied to gender, age, caste, class, ethnicity, and disability tend to exacerbate and solidify in the aftermath of such events. How can that be addressed? The answer might be in how Disaster Impact Metrics – quantitative measurements that evaluate the effects of a specific disaster within a defined spatial and temporal scope – are conceived and incorporated into risk-assessment policies. We talked with Fabrizio Nocera and Chenbo Wang, researchers part of a wider team that also includes Gemma Cremen, Leandro Iannacone and Roberto Gentile from UCL, and Vibek Manandhar from the National Society for Earthquake Technology, Nepal, about how Tomorrow’s Cities is addressing this challenge.

“Part of my work has been looking into a dataset collected near the Kathmandu valley after the 2015 Kokhana earthquake. What we found is that, by designing recovery policies using as the single criteria the physical damage to households, these policies are in fact failing the purpose for which they were designed for. This issue is so relevant that 5 years after the earthquake there were around 10 to 12% of people still living in damaged, unrepaired homes despite the grants given by the Nepalese government for reconstruction.”

Chenbo Wang, PhD candidate, UCL

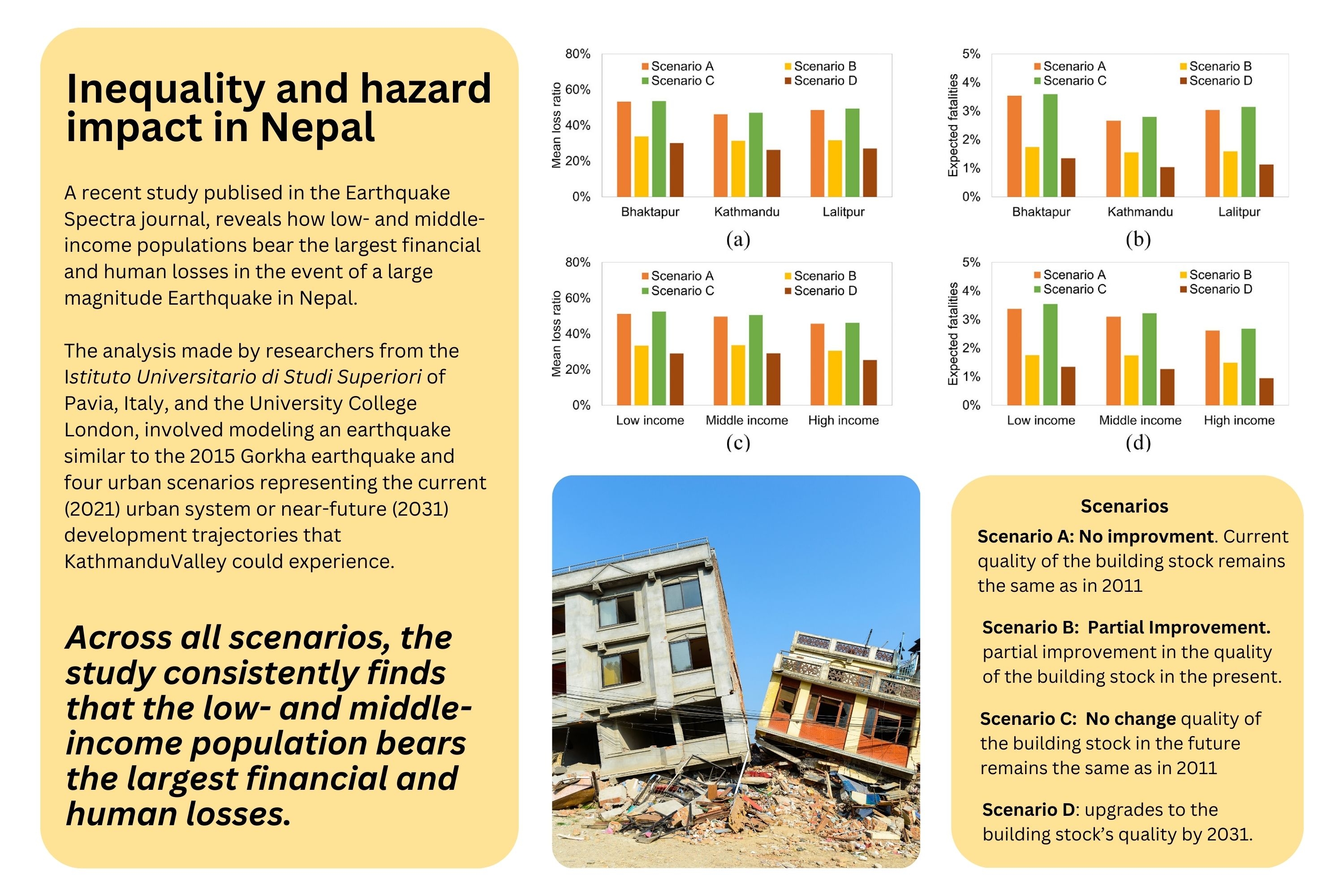

Carlos Mesta, David Kerschbaum, Gemma Cremen and Carmine Galasso authored a 2023 study that shows how low- and middle-income populations are more impacted by earthquakes in Kathmandu.

Tomorrow’s Cities method of dealing with Impact Metrics extends beyond assessing physical damage (damage to infrastructure such as buildings or water supply) or measuring impact in terms of financial losses, to encompass the intricate interconnections between the physical and social systems that underpin a city. Delving into how these elements are interconnected, the ways in which people utilize the infrastructure, and the resultant disruptions to both infrastructure access and the services they provide in case of a disaster, Tomorrow’s Cities is able to better inform policy design. Fabrizio Nocera explains:

“Take access to a hospital in the case of an extreme event such as an earthquake, for instance. Typical approaches to risk-modelling calculate the damage to the residential building that the person inhabits, the hospital and to the transportation infrastructure to reach that hospital, assuming that accessing it is an important aspect. We go beyond. We inquire –whether accessibility to the hospital holds genuine significance for those affected.”

Fabrizio Nocera, Research Fellow in Multi-hazard Risk and Resilience Engineering, UCL

By evaluating the significance of these impacts the team can direct its efforts into mapping and assess the most relevant impacts to those affected by a particular event. It also enables them to enhance predictive models, as different methods of calculation are necessary depending on the impact metrics under consideration. But how exactly is Tomorrow’s Cities finding out about the relevancy of the impacts to the different groups that live in a city?

Mapping relevant impacts to design effective policies.

Aiming at finding out how hazards impact different stakeholders, the Tomorrow’s Cities team designed a survey that directly asks them how they perceive their context, the hazards that affect them and what their priorities are in case of disaster.

“Rather than making assumptions, we actively engage with the individuals most likely to be affected by a specific hazard. We do this by directly asking them whether a particular impact is relevant to their circumstances. This way we gain insights into their priorities that inform the selection of context-specific impact metrics but also the methods we use on our computational simulations, ensuring that our modelling efforts are not only accurate, but also tailored to the nuanced realities and concerns of those directly affected by the hazards in question.”

Fabrizio Nocera, Research Fellow in Multi-hazard Risk and Resilience Engineering, UCL

This strategy was applied in Kathmandu where a survey engaged 90 participants from various backgrounds such has residents, consulting firms, construction and contractor companies, government departments, and insurance companies. They also ensured representativity across all demographic and socioeconomic categories and captured information such as age, household income and size, number of individuals with special needs, number of elderly residents, number of individuals under 18, housing tenure status, housing type, occupation, and education level. This detailed approach aimed to capture a nuanced understanding of the community, ensuring a thorough representation of the diverse perspectives and circumstances present in Kathmandu.

Impact survey deployment in Kathmandu.

“In Kathmandu, we found that the most relevant concern is access to drinking water independently of how long it has passed since the event, which is something that we often overlook. In fact, there isn’t much work done on the impact of a disaster-event on people’s access to drinking water.”

Chenbo Wang, PhD candidate, UCL

Chenbo stresses that the scarcity of studies in this domain can be attributed, in part, to the predominant focus of risk and impact metric analyses on developed countries. In these contexts, where robust water networks ensure the availability of drinking-grade water, researchers may not prioritize the examination of water access as a relevant impact. However, this perspective overlooks the distinct challenges faced by developing countries, where the availability and quality of drinking water are critical concerns post-disaster. The limited attention to such issues underscores the necessity for context-specific analyses that consider the unique circumstances and vulnerabilities of different regions, emphasizing the importance of a more inclusive and comprehensive approach to disaster impact assessments.

Completed surveys and its participants together with the NSET facilitators team.

Creating a Toolbox for disaster impact metrics assessment

The work done by our researchers is now included in a toolbox designed to aid in the development of inclusive disaster risk reduction policies, grounded in the specific context and challenges of the region and based on community feedback.

This toolbox includes a pool of Disaster Impact Metrics (DIM) based on a comprehensive literature review of disaster impacts across various contexts and that capture disaster consequences far beyond direct physical damage or financial losses. For example, they include the effects of losing access to food at the household level, two weeks after the disaster; loss of access to drinking water at the neighbourhood level, six months after the disaster, amongst other impacts across different time scales. It also includes a framework to facilitate the appropriate selection of DIMs from this pool - or the development of novel DIMs - by means of a questionnaire that captures stakeholders' disaster-impact perspectives, such as those used in Kathmandu. The questionnaire results are then statistically analysed through a user-friendly web application that facilitates communicating the results on a later stage.

In Kathmandu, results show that the foremost concern, ranking at the top of the toolbox list, is access to drinking water. However, in other regions, that might be workplace access or the continuity of children's education instead, highlighting the importance of context specific assessments. The toolbox addresses those issues but also how priorities change across different scales—be it at regional, neighbourhood, or household levels—ensuring inclusivity across different groups.

Designing inclusive disaster-risk reduction policies.

As demonstrated by Tomorrow’s Cities research, obtaining information on stakeholders’ priorities is crucial in designing inclusive disaster management policies. Still, how can we ensure that we are not leaving anyone behind?

“To evaluate the effectiveness of a specific policy, we can analyse the data for a low-income group and compare it with other groups of higher income. Consider post-earthquake relocation. We can analyse population relocation data by income intervals. If we notice a disproportionately higher number of low-income individuals being relocated compared to their higher-income counterparts or even in relation to the average relocation figures, we can infer that the policy lacks a pro-poor and inclusive orientation, and we must correct it.”

Chenbo Wang, PhD candidate UCL

This work is part of a parallel research involving a team of UCL/Tomorrow’s Cities researchers such as Gemma Cremen and Carmine Galasso. Their work aims to quantify the relative "pro-poorness" of various policies in response to household relocation following major earthquake events, such as that that rattled Nepal in 2015. Using a virtual urban test model named “Tomorrowville” and simulating ground motion - the vibrations, oscillations, and movements of the Earth's surface resulting from the propagation of seismic waves, which can be used to assess the severity of damage in a specific region – for a plausible hypothetical M7.0 (moment magnitude) earthquake, the team observed that soft policies (e.g., the provision of livelihood assistance) demonstrate greater effectiveness in protecting the most vulnerable populations than those that focus on strengthening the physical facilities within the built environment. These observations can help policymakers, urban planners and local authorities in designing cities which protect more people against hazard events.

The disparity in recovery journeys of individuals, as observed by our researchers in the aftermath of Nepal's earthquake, probably echo similar experiences in Turkey and Libya, two countries deeply affected by significant disasters last year, as well as numerous other disasters over the years. As we’ve seen, a contributing factor is the inadequacy of disaster risk management and recovery policies, which often overlook the context of individuals, resulting in a mismatch between their intended goals and the actual needs of those affected.

Tomorrow’s Cities research not only highlights the potential consequences of the misalignment between policy and individual needs, such as heightened inequalities and hindered disaster response, but also offers a solution: context-specific Disaster Impact Metrics obtained by means of a survey assessed by those who are in fact affected by the hazards. By taking this approach, local authorities can implement disaster risk reduction policies and post-disaster response strategies that genuinely address the needs of the population and are effectively prioritising the most vulnerable communities.

Learn more about the Computational Modelling stage.